The five ‘pillars’ of Crop competition against weeds

- By: "Farm Tender" News

- Cattle News

- Aug 27, 2020

- 1047 views

- Share

By Nicole Baxter for the GRDC

View the original article here

On the back of increasing levels of herbicide resistance, researchers say crop competition can be used more effectively to manage in-crop weeds.

University of Adelaide associate professor Gurjeet Gill. Photo: WeedSmart.

Speaking to growers and advisers during a WeedSmart Q&A webinar for a new online Diversity Era course called Crop Competition 101, the University of Adelaide’s Dr Gurjeet Gill says crop competition underpins effective integrated weed management.

“Crop competition against weeds improves the yield of the current season’s crop,” Dr Gill says.

“It also helps suppress the entry of weed seeds into the soil seedbank, which further reduces future weed infestations in subsequent crops.”

Five ‘pillars’

The five ‘pillars’ of crop competition against weeds are:

- high seeding rates

- narrow row spacings

- improved crop competition traits

- superior soil health

- east-west sowing.

Peter Newman, WeedSmart’s western region agronomist, says multiple Australian experiments show higher seeding rates are effective in suppressing in-crop weeds.

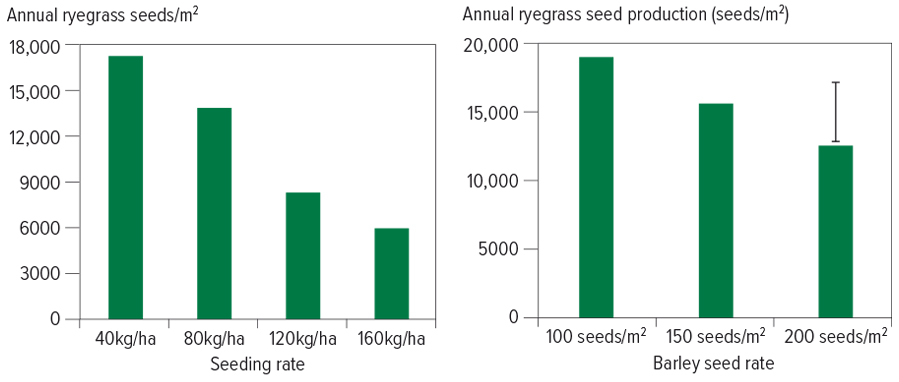

Dr Gill agrees, adding that in southern and western farming systems, weed suppression benefits are often found when cereals are planted at 200 to 300 plants per square metre (see Figure 1 and Figure 2).

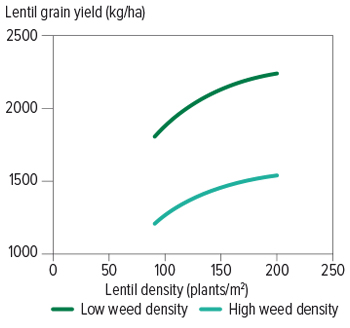

The benefits of higher seeding rates have also been demonstrated in less-competitive crop species such as pulses.

By way of example, Dr Gill points to a trial in which the weakest competitor, lentils, became more weed suppressive at higher seeding rates, which led to a higher lentil grain yield (see Figure 3).

Figure 1: (left) High wheat seeding rates at Mingenew, WA, reduced annual ryegrass seed set. Figure 2: (right) Annual ryegrass production and barley seed rate.

Source: (left) Newman, 2012 and (right) Fleet and Gill, 2018.

Figure 3: High-density lentils are higher yielding.

Source: McDonald et. al, 2007.

Measure seed size

Dr Gill says selecting an appropriate seeding rate starts with careful measurement of seed size.

“In dry seasons or frosted parts of paddocks, wheat might only weigh 27 to 30 micrograms per seed, whereas in favourable seasons it might weigh 40 to 45mg/seed, which equates to a variation of almost a factor of two from one season to the next,” he says.

“Measuring seed weight and adjusting seeding rates accordingly is vital because each variety differs in its seed weight between paddocks and across different seasons.”

Lodging and screenings

While Dr Gill understands the reluctance of people to increase the seeding rate of barley because it carries a high lodging risk, he says wheat is less susceptible to lodging.

“Weed competition benefits with barley can be achieved at a 25 per cent lower seeding density than wheat because it is more competitive than wheat as a species,” he says.

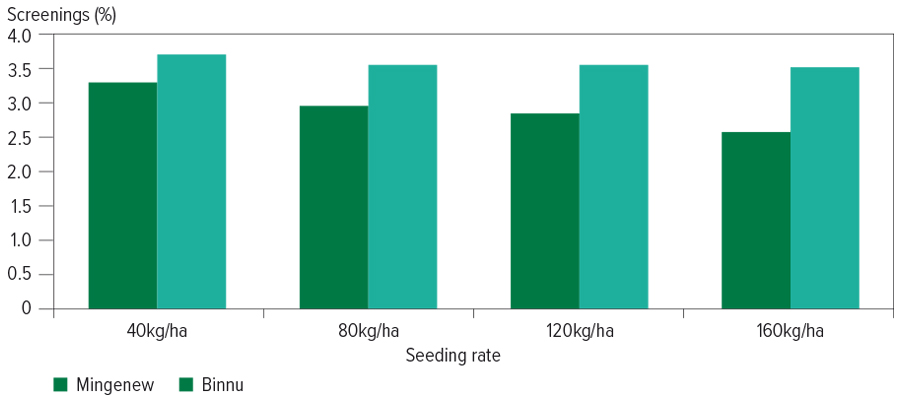

To those worried about increasing the screening risk in dry seasonal conditions, Dr Gill says trials in Western Australia demonstrate a trend toward more uniform seed size with increased seeding rates (see Figure 4), provided nitrogen is managed carefully.

Figure 4: Western Australian trials showed increasing the seeding rate did not increase screenings.

Source: Newman, 2012.

Annual ryegrass

Dr Gill’s research, with GRDC and University of Adelaide co-investment, is exploring the impact of different seeding rates, sowing dates and herbicide treatments on various weeds and grain yields.

“Our research consistently shows delaying seeding to a colder time of the year means the crops are less vigorous,” he says. “As a result, they do not compete effectively with weeds.”

He points to a 2018 trial at Minnipa on South Australia’s Eyre Peninsula where he investigated the impact of sowing time and pre-emergent herbicides on an annual ryegrass population with low dormancy. Weed seeds with low dormancy germinate quickly after rain.

While the use of pre-emergent herbicides almost eliminated ryegrass seed-set, Dr Gill says the results showed the weed seed-set reduction by delayed sowing came at a big cost to grain yield.

He attributes the loss to delayed sowing and the short growing season at Minnipa, which reduced wheat yield by almost one tonne per hectare.

Brome grass

In a 2018 brome grass experiment near Marrabel, north-east of Adelaide, Dr Gill found similar results.

In this study, he explored the effects of different seeding dates, rates and pre-emergent treatments on a dormant population of brome grass.

Although delayed sowing reduced the brome grass population by 40 to 59 per cent, the surviving plants in the later-sown crop went on to produce more seed than in the early sown crop.

The four-week seeding delay not only reduced barley grain yield by almost 1.3t/ha, it also allowed more herbicide-resistant seed to enter the soil seedbank.

“If anybody with weedy paddocks is thinking about a slight delay in sowing to pick up a few more weeds, barley is a safer bet than wheat because it is more vigorous than wheat as a species and finishes earlier,” he says. “With wheat, delayed sowing will not provide beneficial results in most situations, whereas with barley it might, in some.”

Dry sowing

In dry-sowing situations, Dr Gill says a worthwhile approach is to start sowing paddocks with the lowest number of weeds first (based on seed heads observed in the previous spring).

“In some seasons, you may need to dry-seed part of your cropping program, because if the break is late you are really shrinking your grain yield potential by waiting,” he says.

“Sometimes we overestimate how many weeds we can kill with knockdown herbicides, so if the seasonal break is late, a short wait might only give you a 10 per cent weed kill, which is not enough.”

Accordingly, Dr Gill suggests sowing more paddocks dry to take advantage of the warmer growing conditions and using in-crop herbicide options to take out weeds, if they are available.

Row spacing

While many researchers have demonstrated the benefits of narrow row spacing in suppressing weeds, Dr Gill says he understands a shift to narrow row spacing can only be made when seeding gear is upgraded.

Nonetheless, he says, a row spacing of 25.4 centimetres (10 inches) or less should be the goal, rather than 30.48cm (12 inches).

“The evidence from a scientific point of view is clear,” he says. “Wide rows lead to a greater opportunity for weeds to grow and set seed – and that virtually shows up in every trial.”

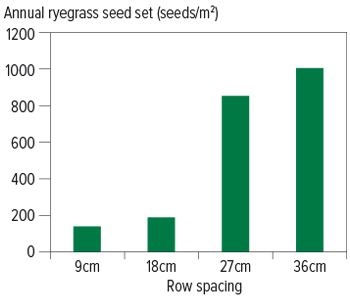

By way of example, Dr Gill points to a long-term (2004 to 2013) study at Merredin, Western Australia, led by the WA Department of Primary Industries and Regional Development’s Glen Riethmuller and Dr Catherine Borger (see Figure 5).

Across all seasons and in every crop, Mr Riethmuller and Dr Borger demonstrated ryegrass seed-set increased when row spacing was wider than 18cm (seven inches).

This is because crops sown in wide row spacings offer less competition for moisture, nutrient and light resources, allowing weeds to grow unchecked in the inter-row.

Figure 5: A long-term (2004 to 2013) investigation of crop row spacing effects on annual ryegrass seed set.

Source: Glen Riethmuller and Catherine Borger, WA DPIRD.

“If we ever needed any convincing of the value of narrow row spacing … here it is,” Dr Gill says.

Soil health

“A healthy crop root system, unimpeded by disease, will acquire nutrients and water, which would otherwise be taken up by weeds,” he says.

“Healthy soils are therefore the vital first step for growing vigorous and weed-suppressive crops.”

Crop traits

Since 2019, Dr Gill says, all breeding companies have had access to the best high-vigour lines from CSIRO’s highly competitive wheat pre-breeding program led by Dr Greg Rebetzke.

“With genetic material now in the hands of breeding companies, wheat varieties will be developed during the next decade, and beyond that they will be adapted to soil types and climatic conditions across Australia,” he says.

“These new wheat varieties should make a big difference in terms of bumping up the competitiveness of our future wheats with weeds.”

But even when these new varieties become available, he says, other weed-competitive tactics such as high seeding rates and narrow row spacings will remain important; and will need to be coupled with careful use of effective herbicides from different herbicide groups.

East-west sowing

Another weed management ‘pillar’ worth considering is east-west sowing.

Mr Newman says researchers in Australia and overseas have demonstrated the benefits of east-west sowing as a tactic to suppress weeds through more shading of the inter-row.

“The further from the equator you are, the larger the effect,” he says. “There are some situations where it can’t be done because of paddock orientation, and plenty of situations where it can, with research showing it can halve ryegrass seed-set.”

Left: Wheat sown in an east-west orientation shades the inter-row, reducing the access of weeds to sunlight. Right: Wheat sown in a north-south orientation does not shade the inter-row and gives weeds full access to sunlight. Photos: Dr Catherine Borger, WA DPIRD.

Putting it together

When it comes to deciding which crop competition ‘pillar’ to apply first, Dr Borger says east-west crop orientation is worth a try because it has been shown to reduce weed set – for free.

“Changing crop orientation will not work in every system, but it is worth considering how this ‘free’ weed competitive tactic could work in your farming system,” she says.

Of the other crop competition tactics, Dr Gill recommends focusing on earlier sowing and higher seeding rates.

“Higher seeding rates do not have to be applied over whole paddocks or whole farms,” he says.

“If you know your zones and have the technology to change your seeding rate on the go, higher seeding rates may only need to be applied to sections of paddocks where weeds are a serious issue.”

Moving to narrower row spacings hinges on having the right seeder, Dr Gill says, which for many farming businesses could be a longer-term goal.

GRDC Research Codes UWA00172, UOA1707-005RTX

More information: Peter Newman, 0427 984 010, petern@planfarm.com.au; Gurjeet Gill, 08 8313 7744, gurjeet.gill@adelaide.edu.au

Watch the video on which this article is based.

The WeedSmart Diversity Era Crop Competition 101 course is free. Visit to register and start the course.

Summer croppers show interest in competition tactics

Among the experts delivering research on crop competition tools in WeedSmart’s online course is Dr Michael Widderick, principal research scientist with the Queensland Department of Agriculture and Fisheries.

Dr Widderick says summer croppers in northern New South Wales and Queensland are showing interest in crop competition as part of an integrated suite of tactics to manage herbicide-resistant weeds.

“We have a range of difficult-to-control weeds and increasing levels of herbicide resistance in a number of our weed species,” he says. “Increasingly, growers are looking for alternatives rather than relying on herbicides alone.”

Early vigour

Generally, Dr Widderick says, grass crops have more early vigour than broadleaf crops and offer superior shading of early emerging weeds.

“Early vigour is important because early emerging weeds have the largest negative impact on crop yield,” he says.

“While grass crops generally provide quicker light interception, over time some pulse crops can compensate and catch up.”

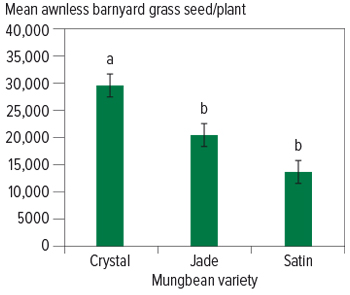

Figure 6: Mungbean cultivar differences in suppressing awnless barnyard grass seed production.

Source: Dr Michael Widderick, Department of Agriculture and Fisheries, Queensland.

Some varieties within certain crop species also demonstrate differences in weed suppression, he says, pointing to an experiment exploring awnless barnyard grass seed production in mungbeans (see Figure 6).

“Where there’s higher canopy cover, we see a greater level of awnless barnyard grass suppression.”

Row spacing

Dr Widderick says the capacity to grow a weed-competitive summer crop depends on available soil water.

“Crop competition is one weed management tactic and you have to weigh up the positives and negatives of applying that to your particular farm,” he says.

“By narrowing your row spacing, you’re going to see improved weed control in-crop and you generally see increases in crop yield. However, in the northern region, I would put a caveat on that and say the increases you see will come down to the resources available for your crop.”

In marginal areas, he says, there is risk associated with moving to narrower rows if the crop runs out of soil water during flowering and grain fill.

Mungbeans, he says, are more forgiving of narrow rows than sorghum, which may yield poorly on narrow rows if there is a moisture deficit at flowering and grain-fill.

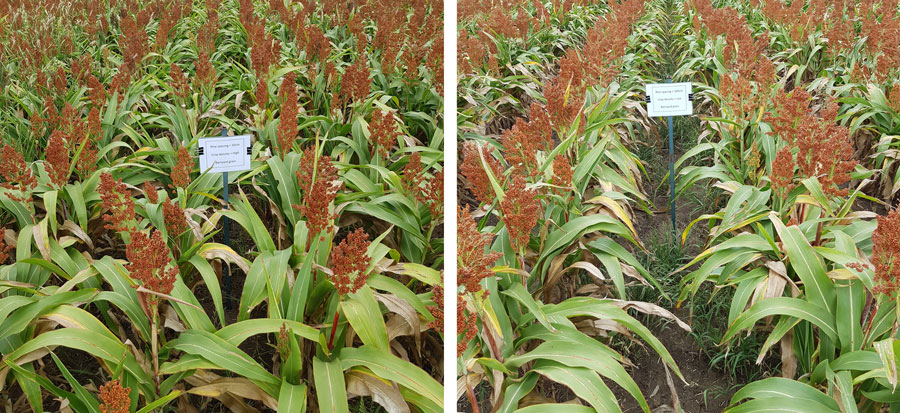

Left: Sowing sorghum on narrow row spacings and at a higher density helps suppress in-crop weeds. Right: Sowing sorghum on wide row spacings and at a low density allows weeds to proliferate. Photos: Dr Michael Widderick, DAF.

Seeding rate

In dryland farming systems in the north, Dr Widderick says a typical sorghum density target is three to six plants/m2. For irrigated systems, he suggests six to 12 plants/m2.

“These figures are based on the amount of water available to the crop and because some sorghum cultivars are not capable of producing more tillers when water is available.”

He says narrow row spacings and increased crop density can have a dramatic impact on the growth and production of weeds in-crop.

“If you can reduce in-crop weed seed production by 50 to 70 per cent, that will have a huge impact on the present crop, but also produce significant flow-on benefits to subsequent crops.”

For northern growers, Dr Widderick says targeting a higher crop density is the first step, while a longer-term goal is to buy a planter set on narrower row spacings.

GRDC Research Code US00084

More information: Michael Widderick, (07) 4529 1325, michael.widderick@daf.qld.gov.au

Share Ag News Via